Irezumi 刺青

Irezumi

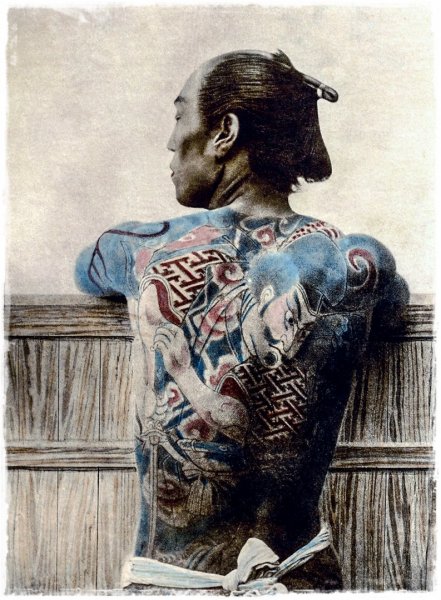

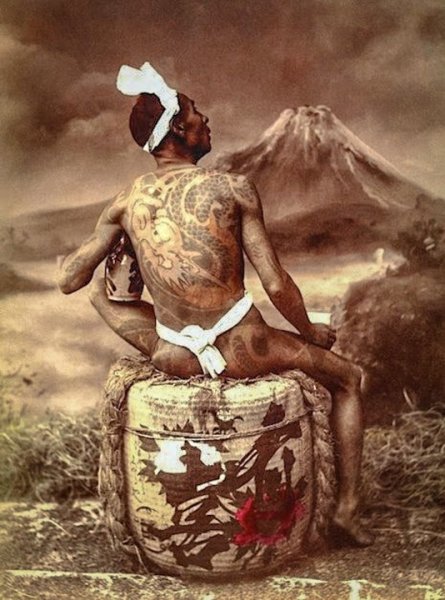

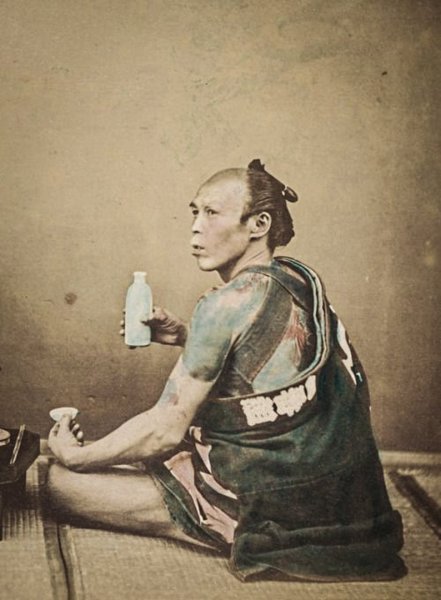

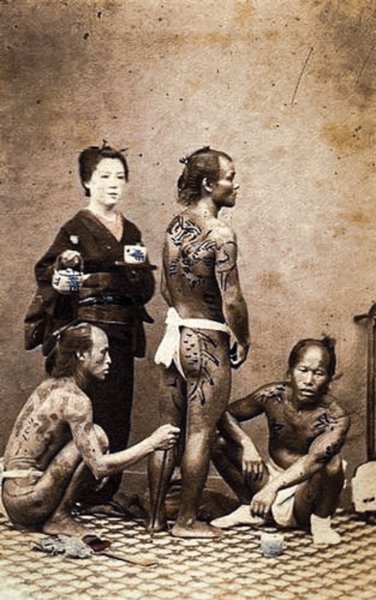

Irezumi (入れ墨, lit. 'inserting ink') (also spelled 入墨 or sometimes 刺青) is the Japanese word for tattoo, and is used in English to refer to a distinctive style of Japanese tattooing, though it is also used as a blanket term to describe a number of tattoo styles originating in Japan, including tattooing traditions from both the Ainu people and the Ryukyuan Kingdom.

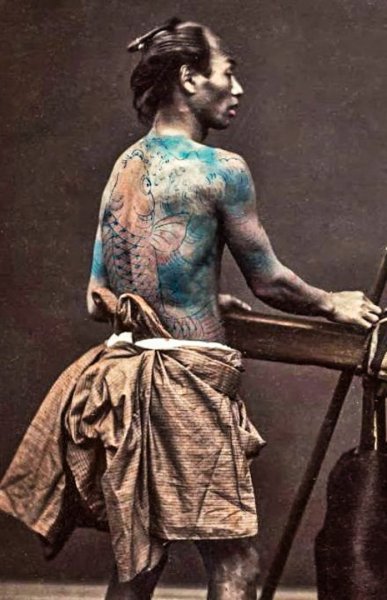

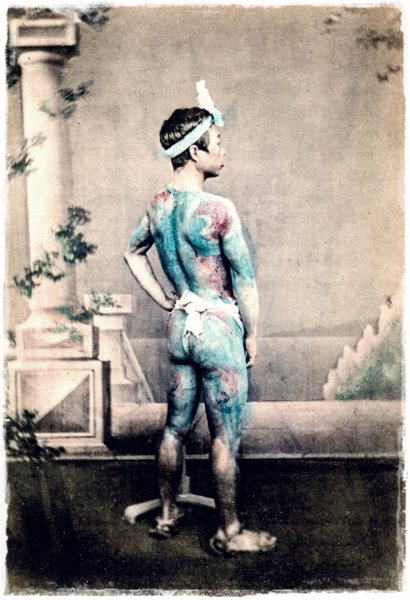

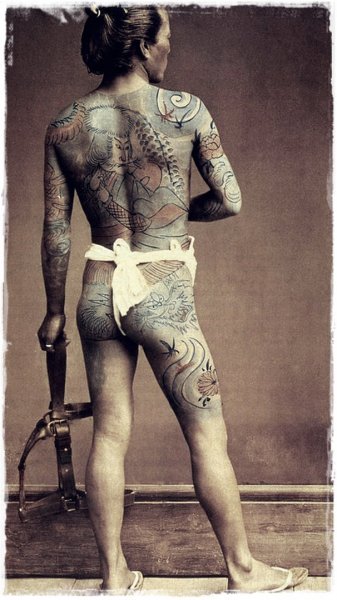

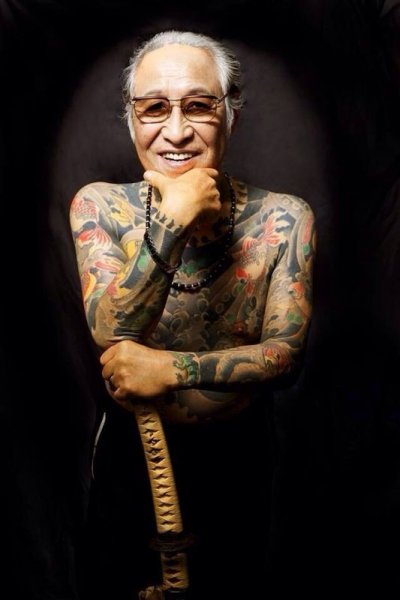

All forms of irezumi are applied by hand, using wooden handles and metal needles attached via silk thread. This method also requires special ink known as Nara ink (also called zumi); tattooing practiced by both the Ainu people and the Ryukyuan people uses ink derived from the indigo plant. It is a painful and time-consuming process, practiced by a limited number of specialists known as horishi. Horishi typically have one or more apprentices working for them, whose apprenticeship can last for a long time period; historically, horishi were admired as figures of bravery and roguish sex appeal.

During the Edo period, irezumi kei ("tattoo punishment") was a criminal penalty. The location of the tattoo was determined by the crime; thieves were tattooed on the arm, murderers on the head. The shape of the tattoo was based on where the crime occurred. Tattoos came to be associated with criminals within Japanese society. Two characters in the 1972 film Hanzo the Razor, set in the Edo period, are depicted with ring tattoos on their left arms as punishment for theft and kidnapping.

At the beginning of the Meiji period, the Japanese government outlawed tattoos, which reinforced the stigma against people with tattoos and tattooing in modern-day Japan.

Etymology

In Japanese, irezumi literally means 'inserting ink' and can be written in several ways, most commonly as 入れ墨. Synonyms include bunshin (文身, lit. 'patterning the body'), shisei (刺青, lit. 'piercing with blue'), and gei (黥, lit. 'tattooing'). Each of these synonyms can also be read as irezumi, a gikun reading of these kanji. Tattoos are also sometimes called horimono (彫り物, lit. 'carving') which have a slightly different significance.

History of Japanese tattoos

Tattooing for spiritual and decorative purposes in Japan is thought to extend back to at least the Jōmon or paleolithic period (approximately 10,000 BC) on the Japanese archipelago. Some scholars have suggested that the distinctive cord-marked patterns observed on the faces and bodies of figures dated to that period represent tattoos, but this claim is not unanimously accepted. There are similarities, however, between such markings and the tattoo traditions observed in other contemporaneous cultures. In the following Yayoi period (c. 300 BC–300 AD), tattoo designs were observed and remarked upon by Chinese visitors in Kyushu. Such designs were thought to have spiritual significance as well as functioning as a status symbol.

However, evidence suggesting a lack of tattooing traditions also exists; according to the early 8th-century Kojiki (古事記, "Records of Ancient Matters" or "An Account of Ancient Matters"), no such traditions of tattooing existed on the ancient Japanese mainland, with people who were tattooed regarded as outsiders. A further record in the Nihon Shoki (日本書紀, sometimes translated as The Chronicles of Japan) (the second-oldest book of classical Japanese history) chronicles that tattooing traditions were confined only to the Tsuchigumo people.

Starting in the Kofun period (300–600 AD), tattoos began to assume negative connotations. Instead of being used for ritual or status purposes, tattoo marks began to be placed on criminals as a punishment.

Japanese tattoos in the Edo period

Until the Edo period (1603–1867), the role of tattoos in Japanese society fluctuated. Tattooed marks were still used as punishment, but minor fads for decorative tattoos, some featuring designs that would be completed only when lovers' hands were joined, also came and went. It was in the Edo period however, that Japanese decorative tattooing began to develop into the advanced art form it is known as today.

The impetus for the development of irezumi as an artform was the development of the art of woodblock printing, and the release of the popular Chinese novel Suikoden in 1757 in Japan; though the novel dates back several centuries before this, 1757 marked the released of the first Japanese edition. Suikoden, a tale of rebel courage and manly bravery, was illustrated with lavish woodblock prints showing men in heroic scenes, their bodies decorated with dragons and other mythical beasts, flowers, ferocious tigers and religious images. The novel was an immediate success, creating a demand for the type of tattoos seen in the woodblock illustrations.

Woodblock artists also began to practice tattooing, using many of the same tools they used for woodblock printing. These included chisels, gouges, and, most importantly, a unique type of ink known as "Nara ink" or "Nara black", which turns blue-green under the skin.

There is some academic debate over who wore these elaborate tattoos. Some scholars say that it was the lower classes who wore—and flaunted—such tattoos. Others claim that wealthy merchants, barred by law from flaunting their wealth, wore expensive irezumi under their clothes. It is known for certain that irezumi became associated with firemen, who wore them as a form of spiritual protection.